My eighth grade English class is almost finished with their drama unit for the year. Right off the bat, I want to clarify that Romeo and Juliet is not my favorite Shakespeare play. Sure, I love a good tragedy, and Othello, Hamlet, and King Lear have always been my top three. However, when faced with a room full of hormonal, emotionally unpredictable thirteen year-olds, Romeo and Juliet always seems like a natural choice. Most middle schoolers are too sheltered to understand Edmund’s pain and Lear’s internal conflict, and are simply unable to keep track of the multitude of characters in Hamlet. I have taught Othello to ninth grade students with success, as it is thematically appropriate for high school, but the overbearing and abusive parents, gender inequality, infatuation and desperation of Romeo and Juliet–eighth graders can actually recognize a lot of these elements in their own lives. Believe it or not, when middle schoolers actually understand the play, they absolutely love it.

Basing a unit upon a text is a big no-no in the current epoch of backward design, but that doesn’t always translate to school and department policies, which often require teachers to use texts by Shakespeare as opposed to other playwrights. Luckily, my BA in theatre arts and (amateur) stage experience leave me well equipped and enthusiastic when it comes to teaching the bard.

My small eighth grade class is made up of merely 13 students, but the majority of students have exceptionalities: 6 have learning disabilities that affect their literacy and critical thinking abilities, 5 are what some may call “mainstream” students, and 2 are considered talented in the discipline of English literature.

Modified for CD (cognitive disability)

Students with cognitive disabilities have trouble with higher order thinking, abstraction, and conceptual understanding. They can be successful in more guided reading and writing, especially when texts and tasks remain at a literal level.

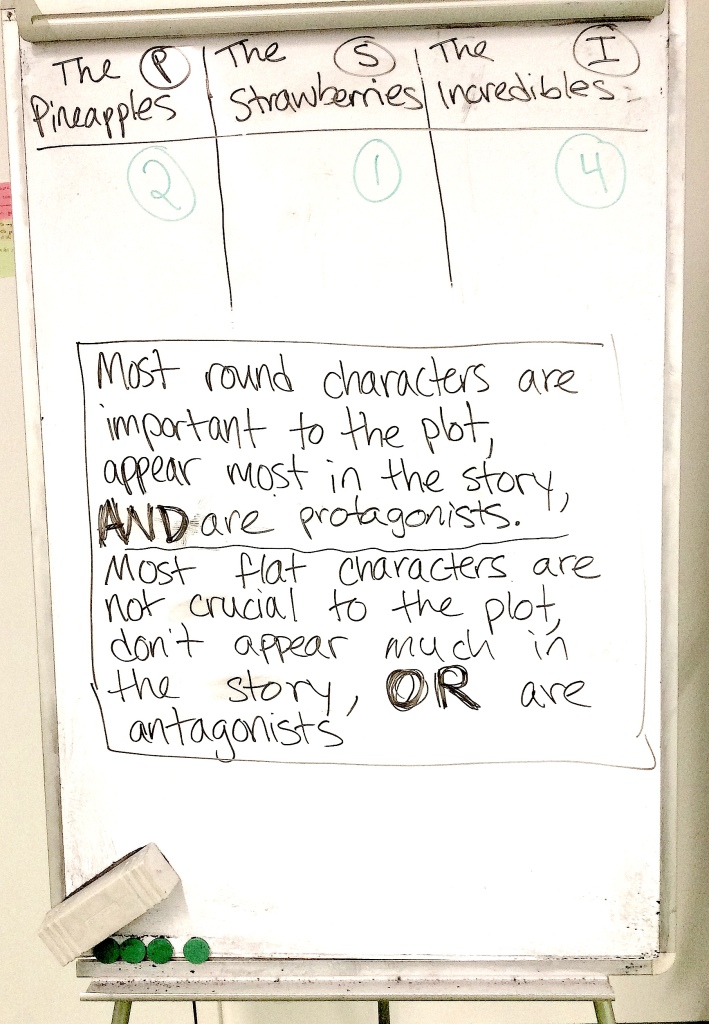

The conceptual question I have these students address is “Why do authors make some characters flat and other characters round?”

Although this can be difficult to answer, we play a game as a class and come up with the conceptual understanding together:

Mainstream

These students must be appropriately challenged with critical thinking, but can be guided through the processes. Some students in this “mainstream” group also have disabilities that affect their literacy skills, but they are capable of higher order thinking and should not be given overly simplified tasks. They either complete essays and are not graded on certain writing skills, or complete oral assessments.

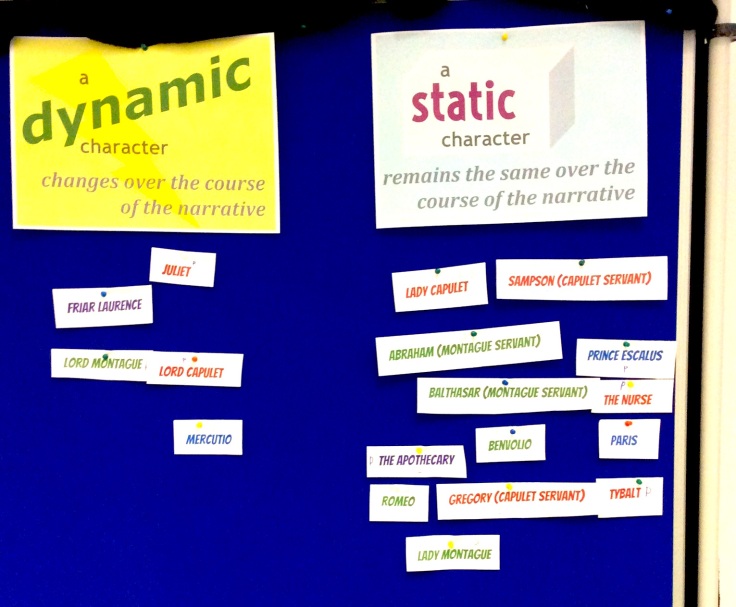

The conceptual question I have these students address is “Why do authors make some characters dynamic and other characters static?”

In order to scaffold this concept, we play another round of the character analysis game:

The difference this time is that I do not guide them to the conceptual understanding. Students are expected to use what they have learned about Shakespeare’s audience and Elizabethan society, as well as analyses they have already done on young adult novels in a previous unit, to write their own thesis statements with guidance.

Modified for GT (gifted and talented)

Students must be challenged in terms of critical thinking and knowledge transfer between disciplines, e.g. history and literature.

This year I worked with two students one-on-one to help develop their theses. One student will interpret the conflict between the Capulets and Montagues as an allegory for the conflict between the Anglican and Catholic church in Shakespeare’s England. The other student will write about cultural relativism in terms of patriarchy and parenting in Romeo and Juliet by the norms of Shakespeare’s society compared with today.

As you can see, by using just one Shakespeare play that young teens can relate to, students can explore one of four (or more!) different concepts based on their abilities. Everyone is appropriately challenged, and nobody’s time is wasted. Plus, grading is a lot more interesting.